Visible Learning Conference with John Hattie…Know Thy Impact

This conference drew delegates from around the world, for an analysis of what is rapidly becoming a global movement. With hundreds of people in the room, Hattie introduced his 3 themes: understanding learning, measuring learning and promoting learning. Throughout the day the reality was that there were other pervading ideas: the SOLO taxonomy was extolled as the holy grail (as a way of moving learning from ‘surface’ to ‘deep’), Dweck’s growth mindset received its’ fair share of positive press, and the benefits of making students struggle (in ‘the learning pit’) was mentioned time and again. Ideas like VAK were given a grilling (“If you hear the name ‘kinaesthetic’ you know someone is talking b******s”).

Keynote 1

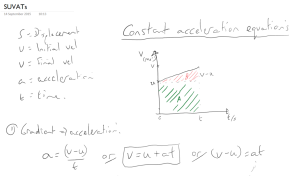

In his keynote speech, Hattie made it clear that the job of the teacher is to facilitate the process of developing sufficient surface knowledge to then move to conceptual understanding. And this is teachable. The structure that this hangs off is the SOLO taxonomy: One idea, many ideas, relate ideas, extend ideas (the first two are surface knowledge, the latter two are deep). Another way of looking at this is that students should be able to recall and reproduce, apply basic skills and concepts, think strategically and then extend their thinking (by hypothesizing etc.)

So that’s surface and deep. Next Hattie described knowledge in terms of the ‘Near’ and the ‘Far’, i.e. closely related contexts or further afield relations – he proposed that our classrooms are almost always focused around near transfer. Hattie finished his keynote speech by briefly outlining 6 of the most effective learning strategies:

1. Backward design and success criteria. ES=0.54 (with ‘Outlining and Transforming’ the most striking at 0.85, although he didn’t really say what this actually meant). More straightforwardly, worked examples are at 0.57 – for me, as a physics teacher, this is critical. Finally, concept mapping entered the hit parade with an ES of 0.64. Hattie then went on to discuss flipped learning, which he seemed quite positive about, perhaps because the effect size of homework in primary schools is zero – which he spun to be a positive: “What an incredible opportunity to improve it”.

2. Investment and deliberate practice. ES=0.51. Top of the table here was ‘practice testing’ (even when there is limited feedback). Hattie thinks that the key to this is that students are investing in effort. “We need to get rid of the language of talent”, including setting etc. Dweck’s mindset work was repeatedly referenced during the day, including an interesting idea about the dangers of putting final work on the walls – perhaps we should decorate our rooms with works in progress? But how do we make the practice that they do ‘deliberate’. Another author repeatedly referenced was Graham Nuthall and his work on needing 3 opportunities to see a concept before we learn it. I thought that it was interesting that Nuthall was given such a glowing report when his book ‘The Hidden Lives of Learners’ includes relatively little in the way of attempting to measure and quantify his conclusions. His conclusion to this section was the catchphrase: “How do we teach kids to know what to do when they don’t know what to do?”

3. Rehearsal and highlighting. ES=0.40. Some strategies here: rehearsal and memorization, summarization, underlining, re-reading, note-taking, mnemonics, matching style of learning (in order of effect size, with the latter at ES=0.17). The key here is to get kids to get sufficient surface knowledge so they can use their (limited) working memory to do the far learning. I thought it was interesting that matching learning styles gets such a bad press when it does, according to this, have at least a small positive impact.

4. Teaching self-regulation. ES=0.53. Reciprocal teaching – not just knowing, but checking that they know why.

5. Self-talk. ES=0.59. Self-verbalization and self-questioning.

6. Social Learning. ES=0.48. The top effect is via classroom discussion (at 0.82) (Hattie stressed that this should not be a Q&A, but an actual discussion).”When you are learning something and you’re still not sure, then reinforcement from classroom discussion is the biggest effect”…but if the discussion is of something wrong, then people are more likely to remember it. The most memorable quote here was that “80% of the feedback in the classroom is from peers…and 80% is wrong”.

Some Q&A

• What about Direct instruction? ES=0.6. The important thing is sitting down with colleagues and planning a series of teachers. And then jointly discussing how you are going to assess it. “If you go out and buy the script, you’ve missed the point”. Constructivist teaching only has an effect size of 0.17. Guide on the side leaves the kids without self-regulation behind. This resonated with the work of David Didau (the learning spy). Interestingly, ‘problem solving’ has negligible effect size, but ‘problem based teaching’ has a large ES.

• And what about IT? Technology is the revolution that’s been around for 50 years and has an ES=0.3. Teachers use technology for consumption purposes, e.g. using a phone instead of a dictionary. That’s why the ES is so low. If you use technology in pairs, then the ES goes up. Why? Because they communicate and problem solve; i.e. use it for knowledge production. Three linked concepts were mentioned: The power of two. Dialogue not monologue. The power of listening. Compare this to the quip: “Kids learn very quickly that they come to school to watch you work”.

• Feedback? The question of feedback is not about how much you give, but how much you receive. Most of the feedback is given, but not received. Students want to know “Where to next?”, so we should show another way, giving direction. This is incredibly powerful. “How do teachers listen to the student feedback voice, to understand what has been received?” This is at the van-guard of Hattie’s current research.

• Error management? Typically errors are seen as maladaptive…and teachers create that climate: solving the error, redirecting to another student, returning the correction to the student who made the mistake, ignore the error (although hardly ever). Hattie sees errors as the essence of learning. He mentioned the teaching resilience as an example of best practice.

Session 1. The Visible Learner with Deb Masters

In her work with John they have developed a model for measuring the effect of feedback and asked the question, how do you take the research and put it into a process in the schools? She called this ‘Visible learning plus’. We were asked to come up with our ideal pupil characteristics: questioning, resilient, reflective, risk takers. And the least ideal: not proactive, defeatist. No surprises there, then.

Deb defined visible learning as “when teachers SEE learning thought he eyes of the student and when students SEE themselves as their own teachers.” So the job is to collect feedback about how the students are learning.

We also need to develop assessment capable learners (ES=1.44). What does this mean? Students should know the answers to the questions…Where am I going? How am I doing? Where to next? Students should be able to tell you what they will get in up-coming assessments.

This workshop slightly lost its way towards the end as time ran out. We quickly looked at the use of rubrics to develop visible learners, and I was struck by the links with the MYP assessment structure.

She finished by looking at meta-rubrics and extolled Stonefields School as an exemplar of this in practice.

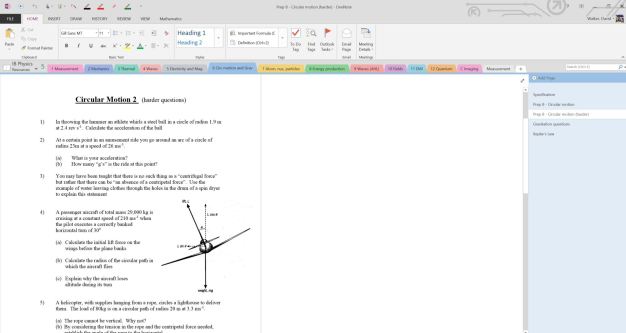

Session 2: SOLO Taxonomy with Craig Parkinson (lead consultant for Visible Learning in the UK)

This is based on the work of Biggs and Collis (1982) and was an interesting and practical session. Much of it was based on the ‘5 minute lesson plan’ (which I remain unconvinced about, despite liking the idea of focusing on a big question). The key is to design and plan for questions that will move students from surface to deep learning (one idea, several ideas, relate, expand). SOLO was the preferred model here, over the well-established Bloom taxonomy. I was sitting next to Peter DeWitt whose blog ‘Finding Common ground’ expands on this.

Session 3: Effective Feedback from Deb Masters

“If feedback is so important, how can we make sure that we get it right?” For feedback to be heard the contention was that you need “relational trust and clear learning intention”. I agreed with the former, but am less convinced by the latter. What do students say about effective feedback? “It tells me what to do next”. Nuthall was mentioned again – 80% is from other kids, and 80% is wrong. Why is there such a reliance on peer feedback? Students say that the best feedback is “Just in time and just for me”…and interaction with their peers is a good way of getting this.

Deb used the golf analogy to discuss the levels of feedback:

1. Self…praise (“cheerleading does not close the gap in performance”).

2. Task…holding the club etc. This is often where teacher talk features the most.

3. Process…what do you think you could do to hit the ball straighter?

4. Self-regulation…what do you need to focus on to improve your score?

The idea is to pick the right level at which to give the feedback…

Can we use the model to help the pupils to give each other and us feedback? I was particularly struck when one delegate from a large school in Bahrain suggested that they are experimenting with the use of Twitter to get instant feedback about the teaching in real time!

Keynote 2: James Nottingham: visible learning as a new paradigm for progress.

James started with a critique of the current labelling practices that occur in schools. For example, every single member of the Swedish parliament is a first born child, and 71% of September births get in top sets compared with only 25% of August births. “Labelling has gone bananas…if you label pupils then you affect their expectation of their ability to learn”.

Eccles (2000): Application = Value x Expectation

Again, progress should be valued rather than achievement. How do we go about getting this…what is the process involved?

The ‘learning pit’ was discussed (Challenging Learning, 2010). Often teachers try to make things easier and easier…the ‘curling’ teacher (push the stone in the right direction and then desperately clean the ice to make it easier for it to go further). I liked that analogy. James (rightly in my view) said that our job is to make things difficult for pupils, after all “Eureka” means “I’ve found it”. I’m sure his book will expand on this, but his basic structure was:

1. Concept

2. Conflict and cognitive dissonance

3. Construct

Some thoughts from the day

• The key message that came through from the whole conference was that everything has to hang off the learning objectives / the learning intentions. Is this just because their research requires a measurement of outcome? This is performance, but not necessarily learning. The question is whether the interventions that Hattie has found apply to effective classroom performance and learning…or just performance? I was struck by the contrast between this and what Didau talks about.

• Throughout the day there was an interesting use of instant feedback – point to one corner of the room if you know about x and the other corner is you don’t.

• Hattie recognizes that we are extremely good at the transfer of ‘near’ knowledge, but not good at the ‘far’…and that is ok: we shouldn’t throw out the baby with the bathwater.

• “It’s a sin to go into a class and watch them teach…because all you do is end up telling them how to teach like you”. You should go into the class to watch the impact that you have.

• What does impact look like at your school? Stop the debate about privileging teaching.

o Can we plot a graph of achievement against progress? This can allow you to make interventions with the drifters.

o How do we measure progress?

o Do we have enough nuancing of assessment levels?

o Hattie: “What does it mean to have a year’s growth / progress? We have to show what excellence looks like. Proficiency, sure, but the key is the link with progress.”

“Visible learning into action” will be out April – June next year to show how this might be put into practice in schools